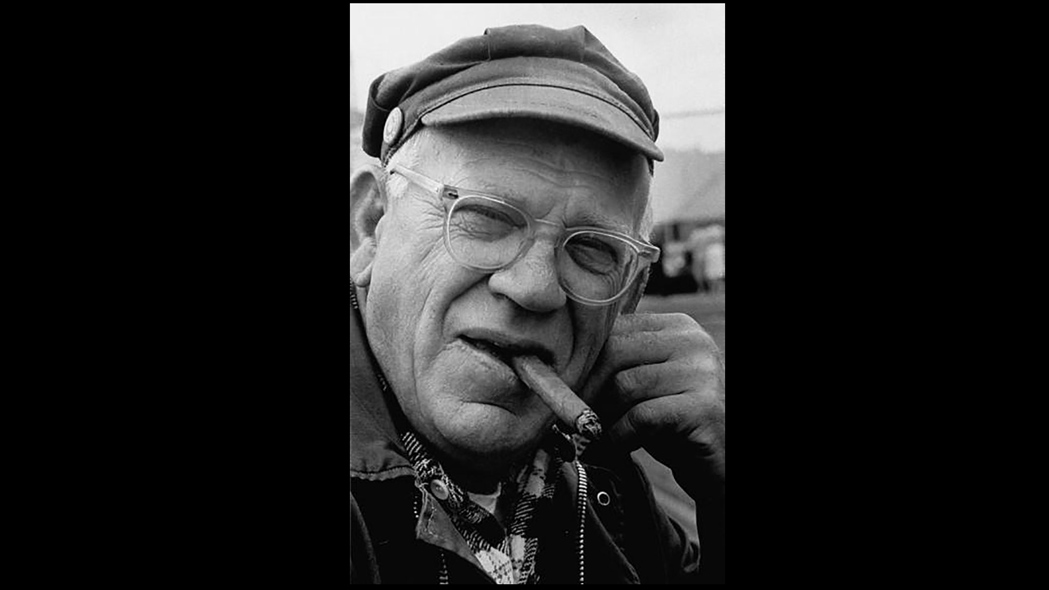

“Faith in a holy cause is to a considerable extent a substitute for the lost faith in ourselves.” – Eric Hoffer

To find the thread that connects Hitler, ISIS and Donald Trump, look for The True Believer by Eric Hoffer (New York: Harper and Row, 1951), subtitled Thoughts on the Nature of Mass Movements.

Hoffer’s analysis of the mind of the extremist, informed by his observations of the totalitarian movements of his day, continues to shed light on our own time. Human nature doesn’t change, and here’s how it works:

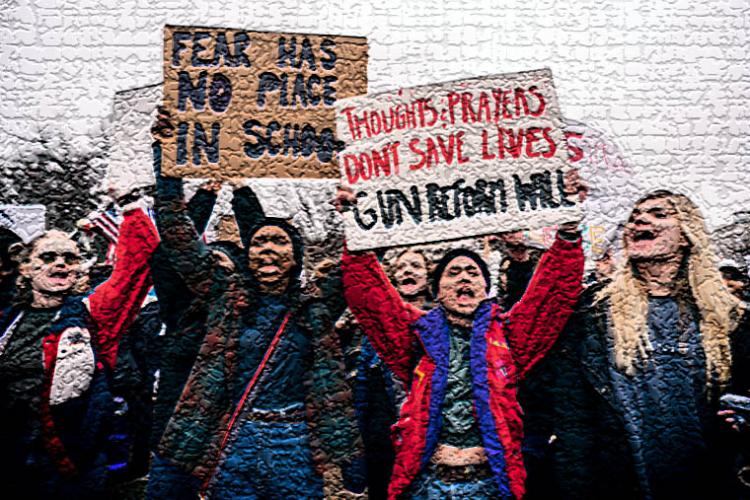

Take a man who is disappointed in love, unhappy with his job (or lack of one) or feeling a sense of fatigue and failure with life in general. Tell this man (or woman) that the problem is not with him, or forces greater than him, but with privileged elites who manipulate him for their own ends. Teach him the rudiments of National Socialism, scientific Marxism or extremist Islam – or just teach him to be angry at someone – and watch his despair and frustration turn to dynamic self-confidence as he undertakes the road to a glowing future by destroying the Jews, capitalism, the infidels or whomever he thinks has thwarted him.

These are the recruits who head off to join ISIS. Happy people do not cut other people’s heads off, but unhappy people might. Yet the dynamics of violent extremism are merely an amplification of our local discontents.

“A man is likely to mind his own business when it is worth minding,” says Hoffer. “When it is not, he takes his mind off his own meaningless affairs by minding other people’s business.”

Hoffer believed that dissatisfaction is not necessarily a bad thing and can be an important motive in human advancement. In his essay, “The Role of the Undesirables” (The Ordeal of Change, New York: Harper and Row, 1963), he argues that the pioneers we admire were not happy, successful people. Had they been, they would never have been pioneers.

Pioneers are people who have failed badly, yet are willing to take a chance, try something new, hit the road. They don’t waste their lives blaming others but, perhaps unconsciously, shoulder responsibility and move forward. Theirs is a constructive dissatisfaction, changing with the world, unlike the destructive dissatisfaction of the extremist, who insists that the world around him must change.

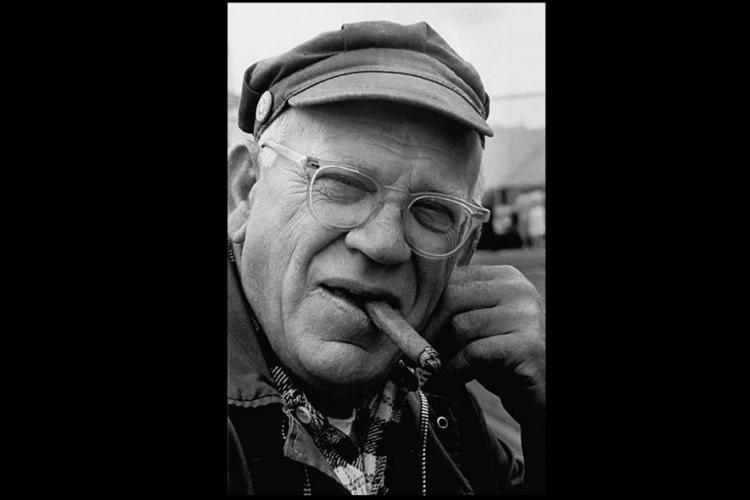

In 1920, at the age of 22, Eric Hoffer hit the road, leaving New York City for the West Coast. A voracious reader, he always kept a library card as he bounced from job to job. During the Depression, he to migrated California’s San Joaquin Valley as a field worker. In 1941, he became a longshoreman in San Francisco, renting a small room near the San Francisco Public Library, and pretty much stayed there for the next 40 years.

That’s it – no academic career, no degrees. He wrote The True Believe in longhand, based on his reading and experience. A literary friend typed it for him and submitted it to publishers. Despite the book’s success, he remained a longshoreman, loading and unloading ships, writing and reading on his own time.

Perhaps his career demonstrates the best foil to the allures of extremism and mass movements: To hell with what other people think or expect; do what you care about – and love.