Every year representatives from a variety of businesses and industries go to campuses all over the country to recruit students. At AWC, students in search of career opportunities go to the Job Fair to hear the presentations of those industry reps.

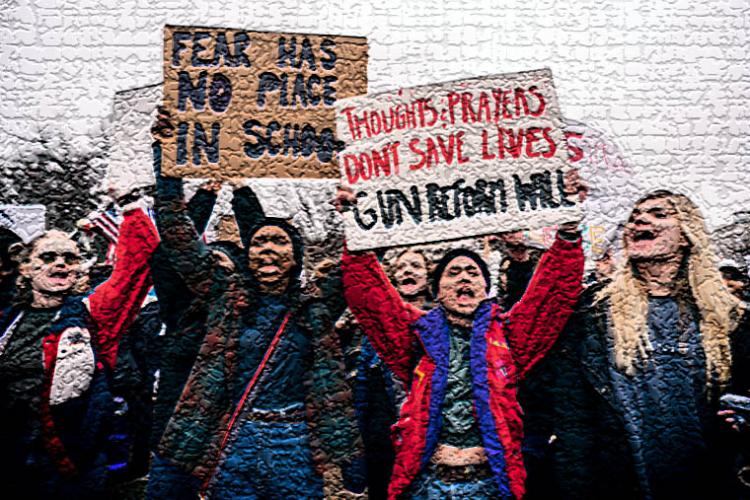

One segment of the Job Fair may cause controversy, though. Three main branches of the military go to job fairs across the U.S. with the goal of recruiting students. Some argue that the military takes advantage of students who might need money to start or finish school by offering to pay for their studies if they enlist. But is this a fair implication?

All branches of the military offer soldiers money to pay for their careers. The Army, for example, has many programs and incentives for soldiers whom decide to continue studying. For one, there is the Army University Access Online (eArmyU), which is a list of online education programs for enlisted soldiers.

The College Loan Repayment program is another way to pay for federal student loans while an individual is enlisted. To receive $65,000 under this program, one must be in active duty for at least three years. Those in the Army Reserve must serve six years and receive $20,000 for education. In addition, the Montgomery G.I. Bill pays soldiers up to $81,756 toward their studies, depending on their career path and length of enlistment.

There is, however, another side to the story. According to research done by Peacework magazine coeditors Sam Diener and Jamie Munro, 57 percent of enlisted personnel have received no help from the military. Diener and Munro say that soldiers who apply for the G.I. Bill must have high test scores and leave the service with an honorable discharge in order to qualify.

Furthermore, the Diener-Munro research says that 95 percent of people who enlist do not qualify for the maximum benefits. Additionally, in order for soldiers to acquire benefit monies of the G.I. Bill, the military deducts $100 a month from their salaries for their first year of enlistment. The money deducted during this time is not refundable, so if a soldier is not eligible for the benefits of the program, he or she loses $1,200.

Diener and Munro also state that, out of nearly 4 million enlisted persons, 1.5 million were on active duty, and only about that same number were able to qualify for the benefits after they were discharged. This left approximately 700,000 former soldiers who were let go with less than an honorable discharge and without the benefits of their money that was contributed within their first year.

Sergeant Peter A. Romero, an Army recruiter, says, “There are different reasons why people join the military – like patriotism, adventure, courage, benefits and a chance to go to technical school.”

“You have to volunteer to be in the military,” Romero says. “There is no one pressuring you to join and nobody is taking advantage.”

Donna Lay, in charge of organizing this year’s Job Fair, says, “I’ve never heard an objection [to the military recruiting on campus] that has been brought to me in the years I’ve been here.”

The two sides of military benefits accrued with service raise a thought-provoking question: Does the military recruit students by offering false hopes, or are the findings of Diener and Munro a big misunderstanding?

One thing is for sure: Students can and should make an informed decision before encountering military recruiters at the next Job Fair.

For more information about military benefits or the research done by Diener and Munro, visit:

http://www.militarybenefits.com or http://www.peaceworkmagazine.org/pwork/0506/050607.htm.