Dr. Corr with 2016 Catrina contestants

La catrina as we know her originated with Jose Guadalupe Posada, considered the father of Mexican printmaking. He became famous for calaveras (skulls or skeletons), images that he wielded as political and social satire, poking fun at every imaginable human folly. His influence on Diego Rivera, Jose Clemente Orozco and other great artists of their generation was incalculable.

La Catrina isn’t your typical revolutionary babe, but her appearance has everything to do with the Mexican Revolution. Posada’s working life paralleled the reign of dictator Porfirio Díaz, whose accomplishments in modernizing and bringing financial stability to Mexico pale by comparison to his government’s repression, corruption, extravagance and obsession with all things European. Posada’s illustrations brought the stories of the day to the illiterate majority of impoverished Mexicans, both expressing and spreading the prevailing disdain for Diaz's regime.

The image now called “La Calavera Catrina” was published as a broadside in 1910, just as the revolution was picking up steam. Posada’s calaveras – La Catrina above all, caricaturing a high-society lady as a skeleton wearing only a fancy French-style hat – became a sort of satirical obituary for the privileged class.

Lineage begins with the Aztecs

The image of the catrina and the woman in death goes back to the ancient Aztec period. Posada took his inspiration from Mictecacihuatl, goddess of death and Lady of Mictlan (the underworld).

Also known as Lady of the Dead, Mictecacihuatl was keeper of the bones in the underworld, and she presided over the ancient month-long Aztec festivals honoring the dead. With Christian beliefs superimposed on the ancient rituals, those celebrations have evolved into today’s Day of the Dead.

Posada’s image was basically a head shot, unclothed except for the elegant hat. It took Diego Rivera to portray a full-length figure, put her in an elegant dress and, by some accounts, dub her “La Catrina.” In the center of his 50-foot mural, Sueño de una tarde dominical en la Alameda Central (“Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in Alameda Park”), Catrina holds the 10-year-old Rivera’s hand while Frida Kahlo in traditional Mexican dress stands behind them. None other than a dapper Posada himself stands to Catrina’s left, offering her his arm. The symbolism – and this is but a fraction – is staggering.

Rivera painted the mural in 1947 at the Hotel del Prado, which stood at the end of Alameda Park. The mural survived the 1985 earthquake, which destroyed the hotel, and later moved across the street to the Museo Mural Diego Rivera, built after the earthquake for that purpose.

Grande dame of death

La Catrina’s vacuously grinning skull fell inevitably into the role of literal and metaphorical poster child for the Day of the Dead, symbolizing the joy of life in the face of its inevitable end.

The Day of the Dead brings into focus one of the greatest differences between Mexican and U.S. cultures – the 180-degree divide between attitudes toward death. Mexicans keep death (and by extension their dead loved ones) close, treating it with familiarity – even hospitality – instead of dread. La Catrina embodies that philosophy, and yet she is much more than that.

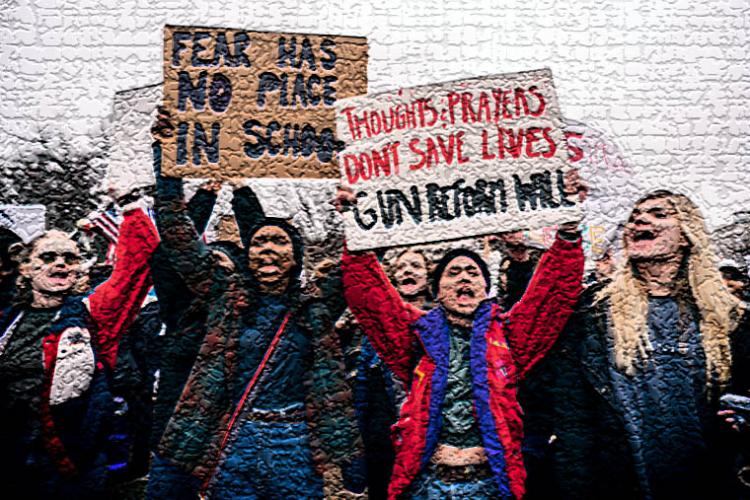

A product of the irreverent spirit and rebellious fervor that ignited a revolution, lovingly kept alive and evolving over time, she remains as relevant today as she was a century ago. She is all the more endearing for reminding us of one more Mexican characteristic that sits 180 degrees from today’s U.S. population – the ability to extract humor from protest and to poke fun at the powers-that-be and sacred cows of any description, with no concern that someone might take offense.

Photo by Ernest Yates