"Öthe common and continual mischiefs of the spirit of party are sufficient to make it the interest and duty of a wise people to discourage and restrain it." -- George Washington, Farewell Address

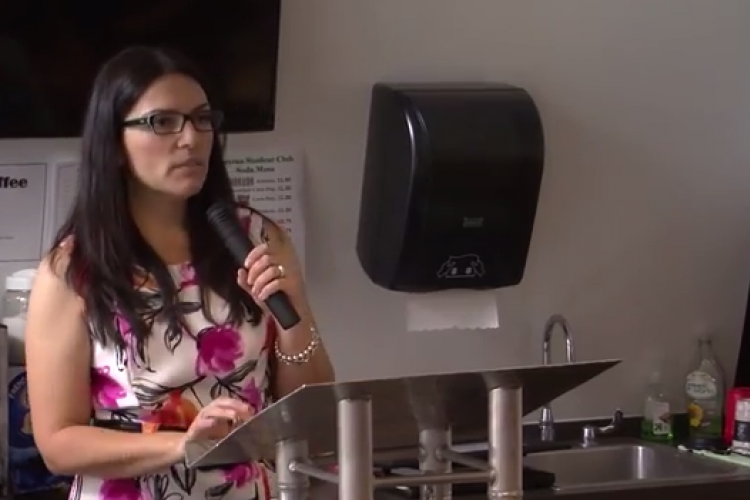

Arizona Western College recently set a good example. Presented with a choice of three candidates for college president, none of whom really fit the bill, we chose none of them. Instead, we asked Dr. Mayle to stay on another year while the search committee continued to look.

We don't always have to accept a bad choice, the lesser of two evils.

This may be a lesson worth applying to our local congressional contest, where right-Republican Ruth McClung is squared off against left-Democratic Raul Grijalva. Both McClung and Grijalva have much to commend them personally: both are "conviction politicians" -- sincere, honorable people.

Unfortunately, you wouldn't always know that from their rhetoric. Mr. Grijalva has denounced SB 1070 as "racist," the hard left's catch-all for anything they don't like. And Ms. McClung, whom supports it, has received -- and accepted -- the endorsement of the Republican Majority Campaign, which denounces Mr. Grijalva as a "dupester" and "communist."

Who needs it?

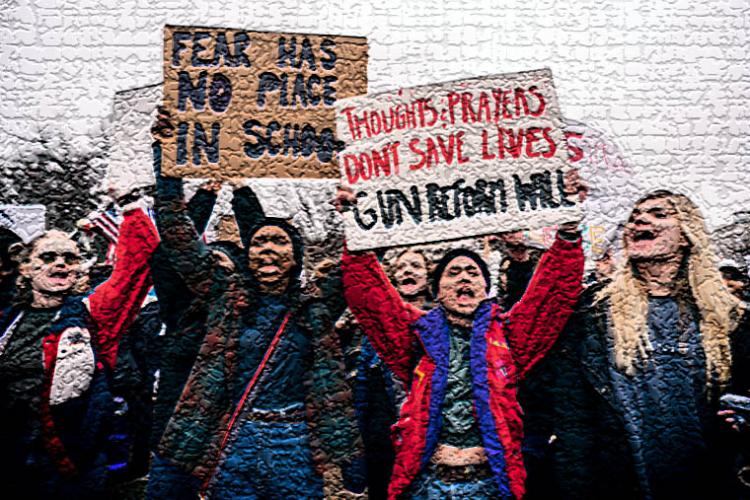

The two candidates illustrate a basic flaw in American democracy. The basic flaw is that political parties tend to be dominated by partisans: people with an answer for everything, often derived from simplistic, ideological formulas fanned by overheated rhetoric. As George Washington observed in 1796, partisan rancor "serves always to distract the public councils and enfeeble the public administration. It agitates the community with ill-founded jealousies and false alarms; kindles the animosity of one part with another; foments occasional riot and insurrection."

Unfortunately, independents and party moderates find it hard to compete with true believers. We lack the "fire in the belly" -- the ideological certitude that makes a strong candidate. (To paraphrase Disraeli: I wish I could be as certain of one thing as McClung and Grijalva are of everything).

Yet moderates and independents are important enough that, once candidates have successfully secured their parties' nominations by appealing to the base, they immediately pivot to the center: "Nobody here but us pragmatic problem-solvers!" And while voters scorn the cynicism of this time-worn, transparent maneuver, are we any less cynical when we accept it by voting for the "lesser of two evils"?

There is an alternative: none of the above.

Perhaps, if enough people reject the choice itself, political analysts might notice that fewer votes were cast in this highly polarized race than in others.

Then, when either Grijalva or McClung goes down in November, as one of them must, pundits may attribute the defeat, in part, to moderate/independent abstention. Thus centrists might begin to thwart partisan control of politics.

Let's do it for George.